BLUF:

The new “Scaled Hypersonics” critical technology area marks a shift from exquisite, low-volume hypersonic prototypes to weapons that can be built and fielded in quantity. Budget decisions in FY25–26 show money moving toward smaller, more manufacturable systems such as Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM) and new efforts like Blackbeard Ground Launch (GL), while large, high-unit-cost boost-glide programs see tighter ceilings or termination.

Introduction

The United States’ 2025 National Security Strategy, released last week, is the latest signal underlining a shift in the Department of War’s (DoW’s) priorities:

“America requires a national mobilization to innovate powerful defenses at low cost, to produce the most capable and modern systems and munitions at scale, and to re-shore our defense industrial supply chains.”

– 2025 National Security Strategy

In practical terms, this means moving beyond exquisite prototypes and toward mass-produced and lower-cost weapons systems.

Nowhere is this shift more evident than in the realm of hypersonic weapons, where procurement from long-running RDT&E programs has only recently begun in modest numbers. While retained as one of six DoW critical technology areas (CTAs)–priority domains identified by the Pentagon to focus its RDT&E efforts–hypersonics are now being reframed as “Scaled Hypersonics” (SHY). According to Under Secretary of War for Research & Engineering (OUSW(R&E)) Emil Michael, SHY means “fielding Mach 5+ hypersonic weapons en masse to strike targets with unmatched speed, precision, and survivability”.

For commercial industry players and defense professionals alike, the message from the Pentagon is clear: the hypersonics race is about quantity, cost efficiency, and speed of production. The following will discuss the context of DoW hypersonics spending to date, the biggest winners and losers by program and contractor from the shift to SHY, and what to watch in the hypersonics space heading into 2026.

The Hypersonics Push: Big Investments, Modest Returns (2018–2025)

Over the last six years, the U.S. military has poured billions into hypersonic weapons development ($4.7B in FY25 alone according to Obviant data) driven by fears of falling behind China and Russia. Multiple programs were launched between 2018 and 2022 to explore the feasibility of boost-glide vehicles and air-breathing cruise missiles in an effort to find a path to an operationally fieldable hypersonic capability.

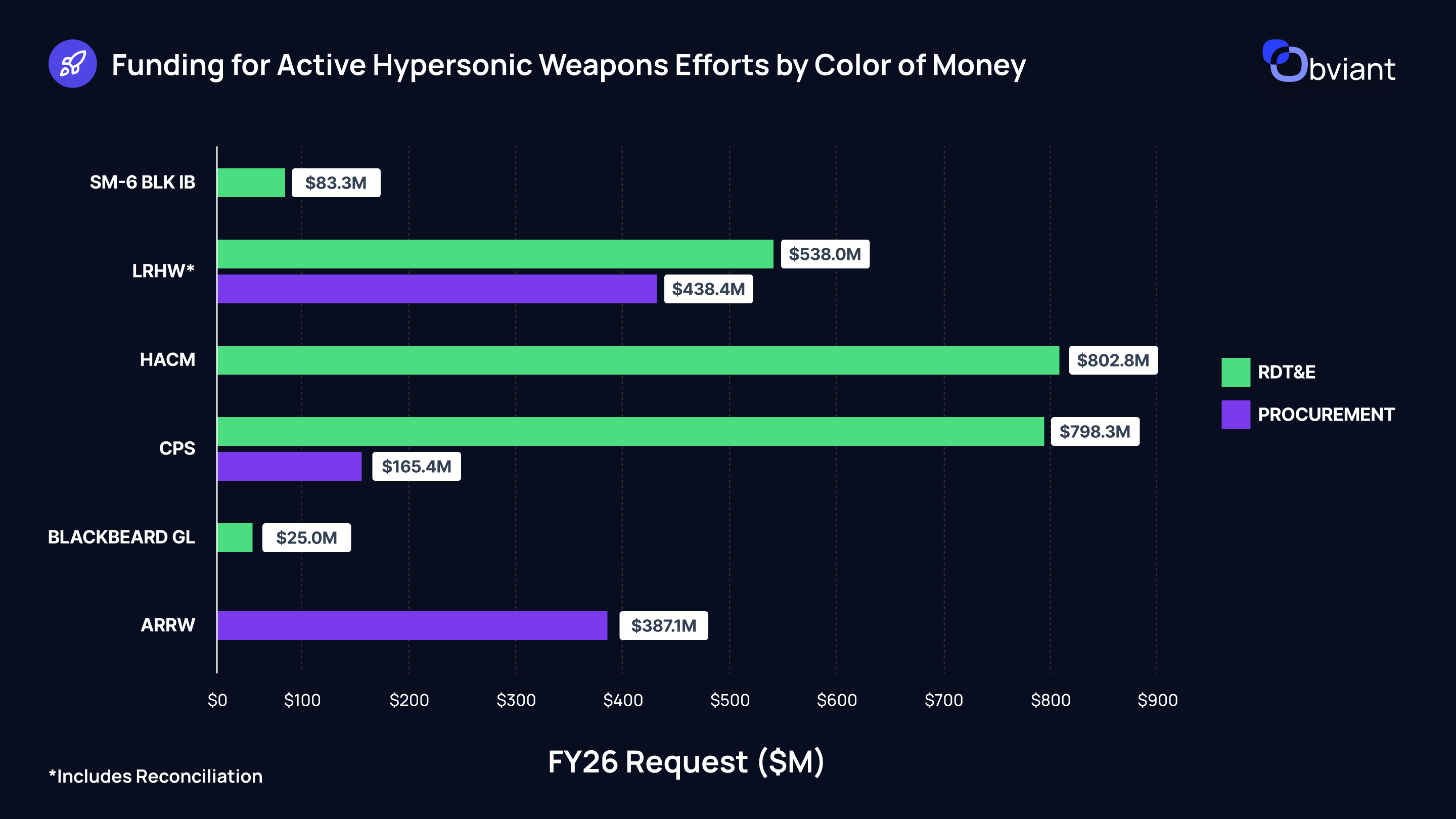

Although RDT&E spending has been high over this time frame, by 2025, the tangible outputs are modest. A snapshot of FY26 illustrates that Procurement across all hypersonics programs this year will be limited ($990.9M total) compared to the $3.1B request for RDT&E.

Across the services, each active hypersonic program has faced challenges and setbacks:

Air Force

- Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW): After a series of setbacks and speculation that the system would never be fielded, the Air Force has included plans to procure an unknown quantity of AGM-183 ARRW missiles in its FY26 request for $387M, though with no follow-on RDT&E funding.

- Hypersonic Attack Cruise Missile (HACM): ARRW’s setbacks informed the Air Force’s shift to HACM, though the smaller, lower-unit-cost missile has faced challenges of its own and is the single-most expensive hypersonic prototyping effort envisioned in the FY26 request ($803M) with no funding for procurement.

Army

- Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW): Also known as “Dark Eagle”, the Army had plans to field the LRHW by FY23. However, several aborted tests delayed deployment to 2025. The FY26 procurement budget includes funding for only 3 all-up rounds and canisters (AUR+C) and associated ground equipment. LRHW also received $85M* in reconciliation funding for procurement (included in figure above).

Navy

- Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS): The Navy ship- and submarine-launched variant of the LRHW is currently undergoing integration efforts with Zumwalt-class destroyers and Virginia-class submarines. Procurement dollars for FY26 ($165.4M) are for support equipment, with no mention of AUR+C procurement in budget documents.

Meanwhile, several other hypersonic efforts have been terminated:

- HCSW: The Air Force canceled its Hypersonic Conventional Strike Weapon (HCSW) in 2020 to concentrate on ARRW.

- HALO: The Navy canceled the Hypersonic Air-Launched Offensive Anti-Surface Warfare (HALO) missile, an air-launched, anti-ship hypersonic concept, in 2025.

- SM-6 Blk IB: The Navy then put the development of the Standard Missile-6 Block IB, a hypersonic-speed ship-launched interceptor and offensive missile, on “strategic pause”, and cut its budget to $83.3M in the FY26 request.

In effect, by mid-2025, the U.S. had procured almost no actual weapons. Senior defense officials openly acknowledge the issue, including hypersonics among a number of “very important technologies that haven’t been scaled yet,” according to Under Secretary Michael.

*$85M in reconciliation for LRHW is derived from the President’s FY26 budget request and is not inclusive of the $400M allocated across LRHW and CPS in the final version of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA).

Winners and Losers: Which Programs Are Aligned with “Scaled Hypersonics”?

Practically, SHY means prioritizing affordability, manufacturing, and supply chain readiness alongside raw performance. OUSW(R&E)’s official description emphasizes delivering hypersonic weapons “en masse”.

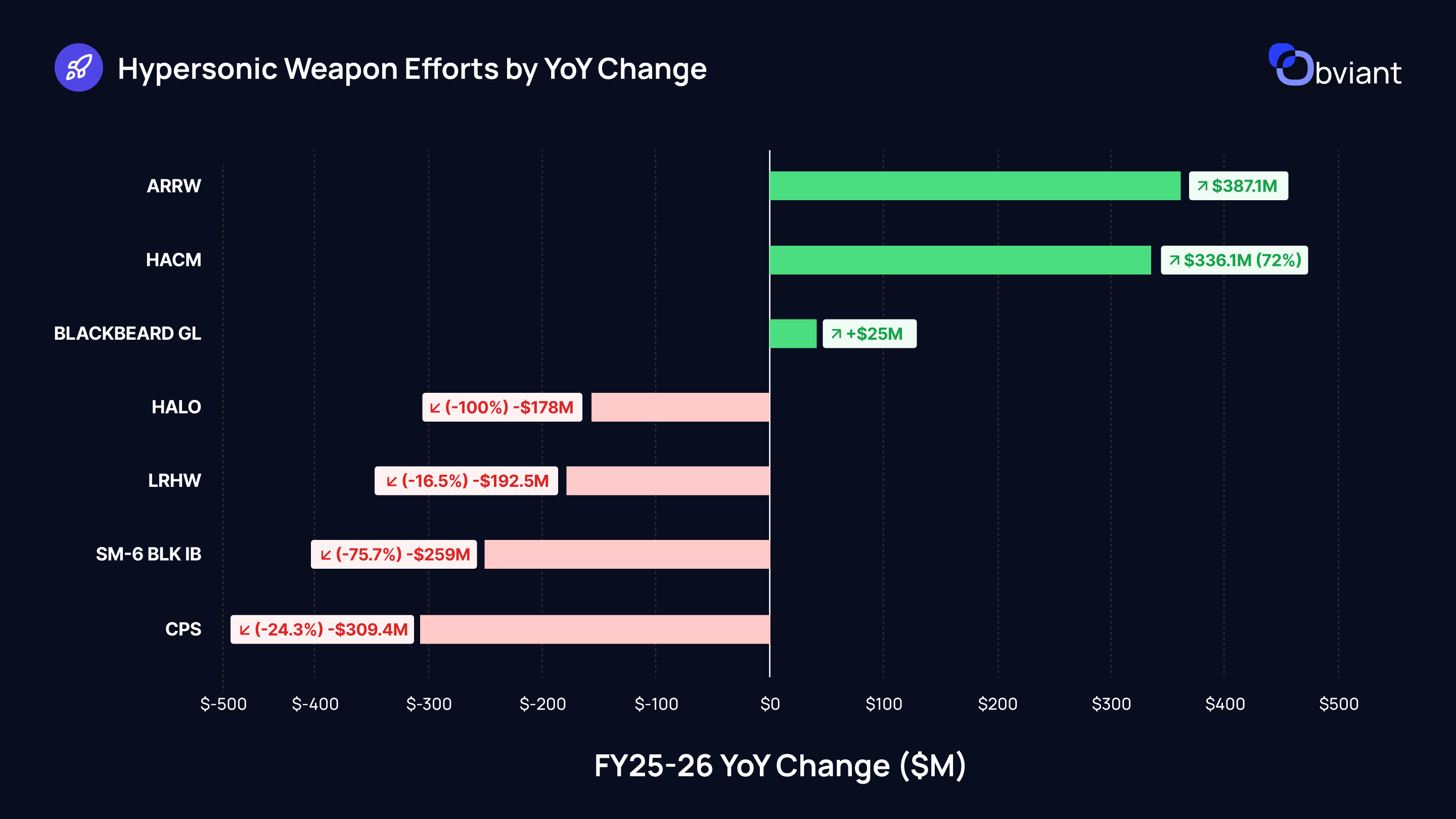

This shift in thinking was already evident in the FY2025-26 budget decisions. Programs with lower unit-cost took precedence, while lower-volume, higher-cost systems were curtailed or canceled.

Program Winners

- HACM: As an air-breathing cruise missile, HACM is smaller than boost-glide missiles and can be carried in quantity by various aircraft. Its dramatic difference in loadout underscores HACM’s inherently higher potential inventory per sortie. HACM and similar “next-gen” hypersonics are being developed with increased production in mind. HACM’s FY2026 RDT&E budget request jumped to $803M (72%), making it one of the largest hypersonic line-items, a strong indicator of where priorities lie.

- Blackbeard Ground Launch (GL): In May 2025, Army leaders approved a requirement for a new hypersonic weapon to launch from a Common Autonomous Multi-Domain Launcher (CAML), a potential replacement for its High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS). That effort materialized as “Blackbeard”, developed by a startup, Castelion. Blackbeard GL is explicitly designed to be cheaper and produced in bulk, with a goal of achieving 80% of a future high-end Precision Strike Missile’s (PrSM) capability “at a significantly reduced cost”. The Pentagon is requesting $25M to develop the system further in its FY26 budget.

Program Losers

- ARRW: Despite receiving $387.1M in FY26 and the Air Force opting to procure an unknown quantity, there is no follow-on RDT&E for ARRW in the unclassified FY26 budget. ARRW’s larger form-factor as a boost-glide system lends itself to lower-volume production. It will provide the Air Force with a strategic, long-range hypersonic capability, but does not necessarily align with SHY.

- LRHW: While the Army is finally procuring and fielding LRHW in FY26, its overall budget has been slashed by $192M (-16.5%) in the request. As an expensive, low-volume, strategic-strike system, it does not align with SHY’s emphasis on scale and affordability.

- CPS: CPS’s budget saw the largest raw decline in its budget in FY26 (-$309M). While the Navy has requested $165M to procure support equipment for CPS, it has yet to complete its integration work and procure CPS munitions.

- Other Navy Hypersonic Programs (HALO and SM-6 Blk IB): The Navy’s HALO program was cut explicitly due to cost and industrial base concerns.The SM-6 Block IB pause likewise reflected an internal assessment that resources might yield better returns elsewhere.

Winners and Losers: What Contractors Stand to Gain in the “Scaled” Era?

The pivot to SHY also inevitably creates winners and losers among industry players.

Winners

On the “winners” side are those contractors aligned with cost-efficiency and mass production.

- Raytheon: Raytheon, which leads the HACM team, stands to benefit if the program transitions to procurement and large orders follow. The Air Force intends to deliver HACM by 2027 and continue development through FY2029, suggesting it views HACM as a future workhorse of its long-range strike arsenal. Importantly, according to Obviant data, the Air Force added a $20M ($90.4M ceiling) “manufacturing capacity enhancement” contract to the HACM effort in October 2024. The contract description bluntly states that “HACM requires an increase in manufacturing capacity of the [all-up-round] and HACM-specific components to achieve expected production rates. The anticipated future production need is greater than what the HACM industrial base is currently estimated to achieve.”

- Castelion: Castelion, founded by former SpaceX engineers, aims to produce thousands of weapons annually and target a unit price in the hundreds-of-thousands of dollars versus the millions or tens-of-millions for current hypersonics. Castelion has won multiple awards for its hypersonic Blackbeard weapon system to be used on Army and Navy platforms and the Army has a $25M budget line in its FY26 request to develop the system further.

- Ursa Major: Ursa Major is building a family of liquid rocket engines for space and hypersonic applications, including the Draper engine, a storable hypersonic system that can be manufactured at scale. The company has secured a $11.8M ($28.6M ceiling) contract from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) “for a tactical flight demonstrator that will prove the ability to use a storable liquid rocket system for hypersonic applications.”

Losers

On the “losers” side are contractors linked to extremely expensive, slow-to-produce hypersonic weapons that do not lend themselves to mass deployment.

- Lockheed Martin: Lockheed was the prime contractor on the ARRW program and is the integrator for the Army’s LRHW and Navy’s CPS systems. The Pentagon’s recent budget decisions suggest a waning appetite for buying boost-glide systems like ARRW (no RDT&E funding in FY26), LRHW (-16.5% YoY), and CPS (-24.3% YoY) beyond current plans.

- Northrop Grumman: While Northrop Grumman also provides the air-breathing scramjet engines for HACM, it and its now-subsidiary ATK Launch Systems are Lockheed’s largest subcontractors for CPS and LRHW ($6.8B in total subcontracts for the missile component used for both systems).

- Dynetics, Inc.: Dynetics, a subsidiary of Leidos, develops and builds the common hypersonic glide body (CHGB) and thermal protection system used for LRHW and CPS. It currently has a $65.8M contract with the U.S. Army through 2029 with a potential ceiling of $670.5M.

What to Watch

- Acceleration of HACM into Procurement: The Air Force is planning flight tests for HACM in FY26. If those are successful, we may see an accelerated timeline to procurement if certain acquisition reforms bear fruit. Also watch for deepening collaboration on HACM between the U.S. and Australia, which has been indirectly involved in some hypersonic research with the U.S. through the Southern Cross Integrated Flight Research Experiment (SCIFiRE).

- Follow-on Contracts with Non-traditional Firms: If Blackbeard GL succeeds in delivering a prototype proof-of-concept this year, they are contracted to produce 10 MVP prototypes by the end of FY26. The next steps could be larger production contracts to begin fielding full batteries in follow-on budgets. Similarly, DoW may begin issuing rapid prototyping awards or Other Transaction Authority (OTA) contracts focused explicitly on production scalability.

- Budget and Strategy Documents Explicitly Referencing Scale: In FY2027 budget J-books and the next National Defense Strategy (NDS), look for language around munitions production and surge capacity specifically related to hypersonics.

Ultimately, scaled hypersonics is about ensuring the U.S. and its allies can deploy overwhelming advanced firepower when it’s needed. As Secretary Hegseth put it, this is to ensure warfighters never enter a “fair fight”. Achieving that with hypersonics will require the manufacturing muscle to build them in large numbers. The realignments happening now are laying the groundwork for a new, scalable hypersonic arsenal.